Oxford's sewage disposal system protects against epidemics

MultakaOxford volunteer Valerii Malko, a philosophy professor from Ukraine, shares his research into the history of public health and sewage systems in Oxford

The problems of city sewage were not originally my area of interest.

In fact, I didn't think much about their significance until 2009 when I visited Southeast Asia, including Penang in Malaysia, Phuket in Thailand and Bali in Indonesia. It was there I first saw some sewage drains running through the centre of — rather than under — the street.

This was my first encounter with city sewers.

The second was when I visited the Alice in Typhoidland display at the History of Science Museum in Oxford.

There is a relatively small amount of information presented in Alice in Typhoidland, and it made me want to find out more about this aspect of Oxford’s history.

And I discovered some fascinating facts.

Population pressures on public health

The 1600s-1700s CE in Britain saw rapid population growth in many cities, leading to widespread public concern about the urban environment and sewage systems.

In most cities, drainage systems and sewage disposal presented a significant challenge. Until the late 1700s CE, sewage collected in domestic cesspools and drained through open gutters.

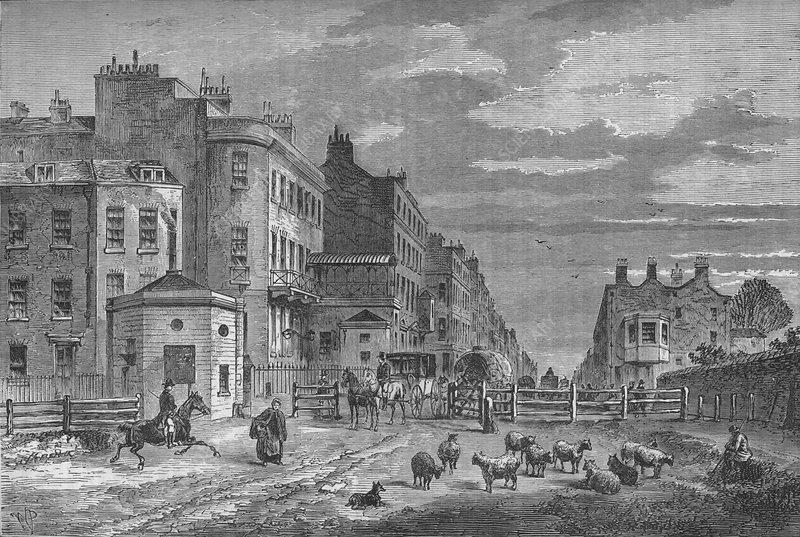

This scene of Tyburn High Street, London in 1820 shows the dire state of one of the capital’s main streets.

Old view of Oxford Street, London. Unknown author, published in The Penny Magazine, London, 1837

At that time, the city's sewers and waterways were considered "open drains”. While residents often complained about it, the city council didn't do a very good job of dealing with the growing drainage problem.

Oxford’s epidemics

Oxford experienced the exact same problems.

During the 1800s CE, Oxford saw a series of typhoid and cholera epidemics, caused primarily by the state of the drainage and sewage systems. Up to the end of the 1700s CE, both the collection of runoff from domestic basins and their drainage through open sewers were often located in the middle of the streets.

Typical view of the Castle Street in Oxford in the 1800s CE

Most sewage continued to be discharged directly into rivers, much of which was upstream of the intake near Folly Bridge.

During the cholera outbreaks of 1832, 1849, and 1854, this became a major problem.

After the first epidemic, an independent commission on health issues was established, which included representatives of the city, university, and parish.

They worked together with the Road Construction Commission, which became the official body responsible for sanitary duties related to the epidemic.

During this period, the Oxford Road Covering Act of 1835 did tackle some public health risks by banning certain activities, such as the slaughter of cattle in the streets.

However, this was not enough to combat the spread of cholera and other water-borne diseases such as dysentery and typhoid.

Collaboration of Town and Gown

The sources also indicate that the campaign for sanitary reform in Oxford was a rare collaboration between the city and the university.

I found it difficult to understand how, in a city like Oxford, the local authorities were not used to working closely with the University.

I decided this could form the next step in my research.

The drive for public health reform

During the 1800s CE, there was a group of people actively driving forward public health reform, including:

Dr Henry Acland, professor of medicine and public health advocate, who created maps recording cases of cholera and typhoid in 1856

and

Oxford's Chief Engineer at the time, William Henry White, who led the survey and reconstruction of the city's drainage system.

Another prominent member of this group was the Dean of Christ Church College, Henry Liddell (whose daughter Alice inspired Alice's Adventures in Wonderland).

Dean Liddell used his position and influence – combined with the spectre of typhoid – to press for the speedy implementation of reforms.

Nonetheless, public health reform proved to be a long process.

It was only after parliamentary approval and threats from government health inspectors that the city council began to consider implementing the Health Act of 1848.

In 1873, the first contract for the sewer project was signed by all commissions. And it was only at the end of 1880 that the construction of Oxford’s sewage system was completed.

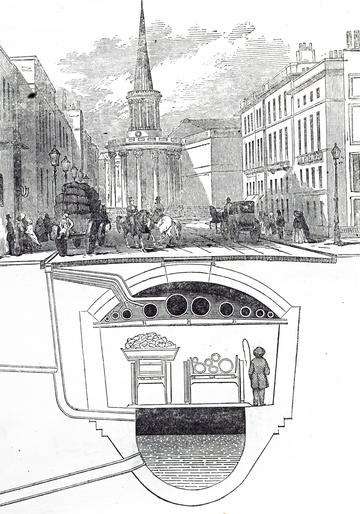

This illustration of a subway used to transport sewage, gas and water is a good example of what works were planned and how Oxford was protected from epidemics.

Strain on the system

Today, Oxford's population of over 160,000 puts a strain on the sewage system.

Every year, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of sewage, sludge, and plastic enter the Thames and its tributaries, threatening public health and the environment.

This situation calls for immediate, decisive action to improve infrastructure and restore clean water.

Hope on tap

In some European cities, it is not possible to drink water from the tap. In the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, for example, that has been impossible for almost 15 years.

In fact, before coming to England, the last time I drank tap water was in Freiburg (Germany) and Karlovy Vary (Czech Republic).

But in Oxford, it is safe to drink water from the tap.

That is why I hope that the authorities carry out this essential work effectively.

November 2024

About the author

This blog post was written by Valerii Malko, a philosophy professor from Ukraine who volunteers for the MultakaOxford participatory research programme on the topic of global health.

MultakaOxford is based at the Pitt Rivers Museum and the History of Science Museum. The project aims to bring people and communities together and to strengthen understanding through intercultural dialogue by sharing art, stories, culture and science in the museums.