Science in the Islamic World

We care for the world's most comprehensive collection of astronomical instruments from the Islamic World.

But what do we mean by 'Islamic'?

Ranging from the 800s CE to the present day, these scientific objects were created and used by people living in lands where the majority religion was — or is — Islam.

While the artisans who made them came from different regions — Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Asia — the objects themselves still share many similar, distinctive characteristics.

And though the instrument makers all lived and worked in the Islamic World, they were not all themselves Muslim.

The result is a fascinatingly rich and diverse collection.

Discover the History of the Islamic World in 11 Maps

Search Collections Online

Search the complete list in Collections Online or find out more about each group of objects

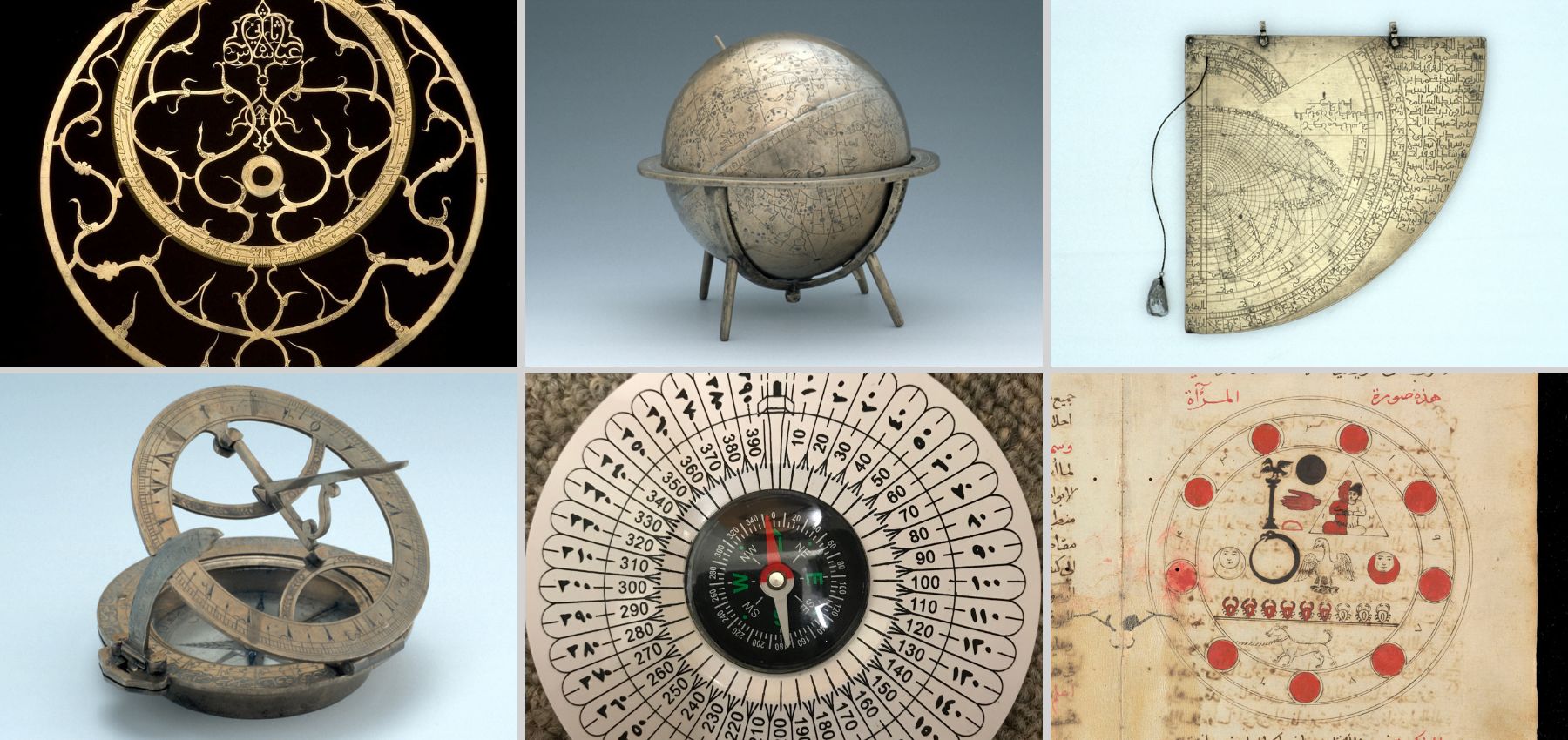

Discover Astrolabes and Quadrants in Collections Online

We are guardians of the world’s most comprehensive collection of astrolabes from the Islamic World

The collection includes the:

- only surviving complete spherical astrolabe

- earliest Persian astrolabe

- earliest complete geared astrolabe.

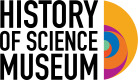

What is an astrolabe?

An astrolabe is a map of the sky, showing the position of the stars on a flat disk.

They were popular for more than 1,500 years; in some parts of the world, they were still in use until the early 1900s. You can use astrolabes to tell the exact time, calculate the hours of prayer, measure height and angles, and even predict the future.

There are two main parts — the ‘star map’ (called a rete) and a projection of the earth’s surface. You can move the rete to imitate the regular movement of the stars above our heads; make one full turn, and a day has passed under your hand.

Beautiful works of art in their own right, each astrolabe and quadrant in our collection has a different set of stars, decorative features and intricate details.

Discover Celestial Globes in Collections Online

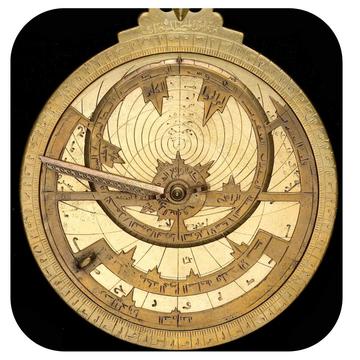

We look after a fine collection of celestial globes from the Islamic World.

Celestial globes are spherical maps of the sky.

With the Earth at their imaginary centre, they show the stars and constellations seen from outside the celestial sphere looking back at the Earth i.e. a “God’s eye” view.

They often have the star names engraved and the constellations drawn in to make them easy to identify.

On celestial globes made in the Islamic World, the head of every human figure is turned towards the observer while the rest of the body “looks” inside. This makes right-handed figures appear to be left-handed, and vice versa (look out for Perseus wielding a sword in the left hand rather than the right).

To explain this difference between a constellation as seen from the Earth and as seen on a globe, the Persian astronomer al-Sufi (903-986 CE) drew two pictures for each constellation in his Book on constellations: one for the terrestrial view with front-facing, right-handed figures, and the other for the mirror-image celestial version — still facing front, but now left-handed.

When in use, globes are usually mounted in a frame, so users can rotate and tilt them to different latitudes. But these instruments are more than astronomical tools and teaching instruments. The technical skill and artistry used to engrave the stars and zodiac signs mean they stand as artworks in their own right.

Discover Qibla Indicators & Sundials in Collections Online

Our collection of qibla indicators and sundials ranges from the 1600s CE to the present day.

Named after the Arabic word for ‘direction’, a qibla indicator is a type of modified compass which Muslims use to determine the direction they need to face to perform their prayers (towards the Kaaba — the sacred mosque at Mecca).

Practising Muslims still use them today, although increasingly in the form of a mobile app. Many of our qibla indicators are lavishly decorated with beautiful engravings.

Search the MSS Stapleton Collection (1-49)

MSS Stapleton (1-49): Alchemical works in Arabic script

The History of Science Museum holds a collection of 49 alchemical manuscripts brought together by Henry Ernest Stapleton (1878-1962), chemist, educational administrator, and historian.

Most of the manuscripts are alchemical treatises in Arabic script — both antique manuscripts and modern copies of originals — dating from 1500 to 1956 CE.

The collection also includes papers and correspondence of Stapleton himself discussing and analysing manuscripts similar to these (1894-1961 CE).

Bring Museum learning alive

Our Learning team offer a great selection of interactive workshops, linked to the National Curriculum, including sessions themed around science in the Islamic World.

Blended learning

Do you want to experience hands-on learning in the Museum galleries?

Or bring the wonder of museum learning into your own classroom?

Talk to our Learning Producers to find the in-person or online learning solution that's right for you.