The travels of an astrolabe: Persia to Afghanistan

Dr Sumner Braund follows the Shah Abbas II astrolabe over two centuries from its origins in the Safavid court of the mid-1600s to its extraction from Bala Hissar in Kabul.

Master of the universe

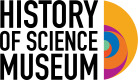

In 1647 CE, Muhammad Shafi’ — the astronomer of Janabad — dedicated a monumental astrolabe to Shah Abbas II, the ruler of Safavid Persia.

Shah Abbas II’s name and prestige were fixed onto the astrolabe’s throne in gleaming brass:

Inscription on the throne of the Shah Abbas II astrolabe (Inv. No.: 45747)

The supreme prince, the sultan, the most just, the greatest, lord of the centres of command, remover of the causes of tyranny and rebellion, king of the kings of the age, Abu-I-Muzaffar Sultan Shah Abbas the Second, the Safawi, the Musawi, the Husaini, Bahadur Khan. May God Almighty perpetuate his Kingdom and his Empire and cause his justice and his benefits to spread over the worlds while the spheres revolve and the planets continue courses.

In every way, this object is a masterpiece:

As the possession of a ruler, it makes a powerful statement: the owner of this astrolabe is master of the known universe, terrestrial and celestial.

So why did Shah Abbas II give the astrolabe up?

An astrolabe on the move

The astrolabe itself tells us that it was made in the Persian empire, for a Persian ruler.

But we know it did not stay there.

In 1879, the British military took the astrolabe by force from Bala Hissar, the fortified palace of Kabul in Afghanistan.

Bala Hissar, Kabul, January 1879. Photography by John Burke. National Army Museum. NAM 1965 03 87 1.

I will explore this painful, bloody, extraction in the next blog post. For now I want to focus on the why the astrolabe was in Afghanistan in the first place, and how it got there.

This question is difficult – but not impossible – to answer. My research is ongoing, and I've reached a stage where I have a few possible scenarios.

There are pros and cons to each – I’d love to know which one you think is the most probable (comments box at the end of this post).

Scenario 1: Palace intrigue

From the Safavid to the Mughal court

In 1647 – the year this astrolabe was dedicated:

Shah Abbas II is the ruler of the Safavid Persia

The Mughal Empire stretches from Afghanistan across northern India and Pakistan

Kabul is one of the host cities for the court of Shah Jahan – ruler of the Mughal Empire and the man who commissioned the Taj Mahal

The Muslim Mughal, Safavid and Ottoman Empires at the end of the 1600s. CC BY-SA 4.0.jpg

Daggers in men’s smiles: coronations and counter-attacks

As you can imagine, powerful emperors make uneasy neighbours. The Safavid and Mughal courts maintained a tense – but cordial – relationship.

Some of the diplomatic missions between the Safavid and Mughal courts are recorded in The Shah Jahan Nama, an account of Shah Jahan’s court written by one of his official historians.

For example, when Shah Abbas II came to the throne, Shah Jahan sent lavish gifts to the new Persian ruler:

Painted portrait of Shah Jahan from the 17th century, from an album of Mughal Indian Paintings and Calligraphy, held at the Bodleian Libraries, Bodleian Library MS. Douce Or. a. 1, fo. 9a

there was dispatched a friendly epistle to the new Shah expressing deep sympathy and sincere congratulations; together with a rare gift of some jewelled articles and 5,000 pieces of various costly manufactures of the imperial dominions.

The Shah Jahan Nama of ‘Inayat Khan, an abridged history of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, compiled by his royal librarian, ed. and trans. W. E. Begley and Z. A. Desai (Oxford: OUP, 1990), p. 338.

Did Shah Abbas II send the astrolabe to Shah Jahan in thanks?

The Shah Jahan Nama does not say explicitly that he did, but it does show that the astrolabe could have moved from Persia to Kabul as part of a diplomatic mission like this one.

Was the astrolabe a spoil of war?

Just one year later in 1648, the two courts were at each other’s throats.

Shah Abbas II had launched a military campaign into Mughal territory in Afghanistan, and in 1649 captured Kandahar before turning his army’s sights on Kabul.

But Shah Abbas II’s foray was unsuccessful. He was forced to leave Kandahar and the region ‘due to the severe shortage of forage for the horses and the similar scarcity of grain for the troops.’ (The Shah Jahan Nama, p. 421).

Was the astrolabe used as ransom for high-ranking prisoners of war during the siege of Kandahar or left behind as the Safavid army retreated?

The power of diplomacy

In 1660, Aurangzeb – Shah Jahan’s successor – received another diplomatic mission from Shah Abbas II’s court, this time characterised by rich gift-giving on both sides1.

Was it on this mission – or another similar one – that the astrolabe made its way to Kabul?

As a gift to a Mughal ruler, the astrolabe would convey many subtle messages:

Its monumental size and elaborate craftsmanship make it a valuable gift – showing great respect for the receiver.

The fact that it is a scientific instrument requiring specialist knowledge to use would also have been a compliment: a gift for a respected and intelligent ruler.

However, a gift can send messages in both directions.

Just as it shows respect for the receiver, this astrolabe also proclaims the wealth and power of the giver. And as an object inscribed with Shah Abbas II’s name, it would have shown both Shah Abbas’ humility in giving and his pre-eminence as a ruler and intellectual.

Scenario 2: A Game of Thrones

Dynastic changes — Hotak and Durrani emperors

There are many ways an object can move from one place to another.

As we have seen, gift-giving is one way for high-status, precious objects to travel from one royal space to another.

Acquisition through conquest is another.

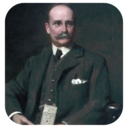

c. 1730 map of southwestern Asia, specifically focusing on Persia, by Reiner and Joshua Ottens (Isfahan and Kandahar highlighted)

Did the astrolabe's owner — and location — change through right of conquest?

From 1709 CE — roughly fifty years after the astrolabe was dedicated to Shah Abbas II — the Hotak dynasty started its rise to power in Afghanistan.

By the 1720s, the Hotaks had extended their power over parts of the Persian empire. In 1722 CE, Mahmed Hotak declared himself ‘Shah of Persia’ and ruled over an empire that stretched from Kandahar to Isfahan.

Did Mahmed Hotak find the astrolabe in the treasury of Isfahan and bring it to Afghanistan?

By 1747 CE, a new dynastic power was growing in Afghanistan.

The Durrani dynasty was named after its powerful leader, Ahmad Shah Durrani. Wrestling control of Kabul from its Mughal governors, Ahmad Shah took power in a vast territory that encompassed Kandahar and much of modern-day Afghanistan.

Did Ahmad Shah Durrani find the astrolabe in one of the Hotak treasuries?

In the 1750s, the Durrani empire extended to the city of Lahore, a favourite site of the Mughal court.

If the astrolabe had found its way into the Mughal treasury (either in Kabul or Lahore), did it become Ahmad Shah Durrani’s property when he conquered these cities?

The motivation of 'maybe ...'

Each of these scenarios presents possibilities, hinting at the myriad ways this astrolabe could have travelled from Persia to Afghanistan.

If you've noticed the many ‘Did this happen?’ questions, that's because — without a document stating ‘the astrolabe was here’ — I cannot be more definitive than ‘maybe’.

It’s a point in my research that is in equal parts exciting and frustrating.

To me, it’s not a dead end. It's an opportunity.

It's the chance to keep many possibilities on the table, and my mind open to scenarios I haven’t yet considered.

Sometimes, though, I do wonder whether ‘none of the above’ explains how the astrolabe moved from Isfahan to Kabul …

Maybe it’s a more mundane story: a new Persian ruler needed funds, and the quickest way to raise these was selling off some of the precious objects in the treasury. And that was the first step on the long and winding road of buyer-seller-buyer that brought the astrolabe to the palace treasury in Kabul.

What do you think about these scenarios?

Are there any others that you think would explain how this magnificent instrument found its way to Kabul?

I’d love you to share your thoughts and join the conversation.

And don't miss the next chapter in the story in my next post, The travels of an astrolabe: Kabul to London.

May 2023

Footnote: 1 Khāfī Khān, Muḥammad Hāshim. Khafi Khan's History of ʿalamgir : Being an English Translation of the Relevant Portions of Muntakhab Al-Lubāb, with Notes and an Introduction (Karachi: Pakistan Historical Society, 1975), p. 130

About the author

Dr Sumner Braund

I’m a historian of early medieval England with a passion for museums and archives.

As Research Fellow on the Finding and Founding Project, I am putting investigative skills to work as I uncover the provenance history of the History of Science Museum’s founding collection.

This work has already taken me to archives in the UK and the US, from nineteenth-century letter collections to sales registers to military dispatches.

For me, history is the study of people – and the objects that I am currently investigating are taking me on a global journey to people past and present.

Share on social media

If you'd like to share this post on social media, just copy this link:

https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/finding-and-founding-blog-three-the-travels-of-...

and go to your chosen social media channel:

Comments

As always, we’re interested to know your thoughts, so please share your comments with me: